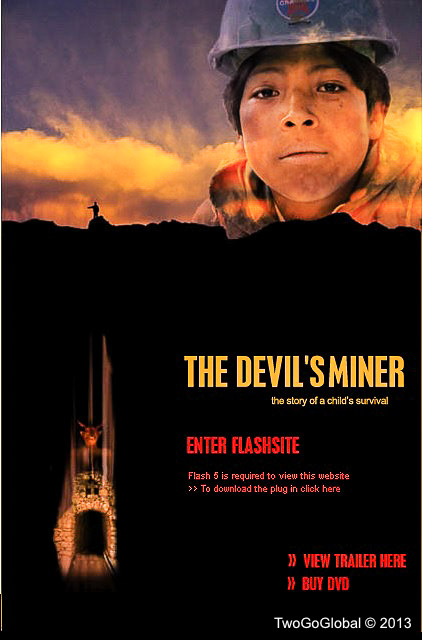

Prior to leaving Sucre we watched “The Devil’s Miner”, an eye opening American/Austrian documentary about two young brothers, one ten years of age and the other fourteen. Both ended up working deep inside the mines after their father died at an early age – they became the family breadwinners having to support their sister and mother. There are still around eight hundred child miners in this situation! Most of them end up in an early grave with a life expectancy of 35-45 years dying from either cave-ins or Silicosis.

“Near the mountain city of Potosi in the southern highlands of Bolivia, the cone-shaped peak of Cerro Rico stands as a 15,800-foot monument to the tragedies of Spanish conquest. For centuries, Indian slaves mined the mountain’s silver in brutal conditions to bankroll the Spanish empire.

Today, the descendants of those slaves run the mines. But hundreds of years of mining have left the mountain porous and unstable, and experts say it is in danger of collapsing.

At a recent meeting of engineers and Quechua Indian co-op owners who run the mines, Nestor Rene Espinoza unveiled a three-year study of the mountain. Espinoza, an engineer, says there are 600 mines, most of them abandoned, and about 60 miles of shafts that have left it hollowed out like a slab of Swiss cheese.

“Total collapse is possible,” Espinoza says. “We hope that this does not happen in Cerro Rico.”

His proposal, to pump tons of concrete into abandoned shafts, is now being considered. But the fact that some are questioning the very viability of the Cerro Rico is no small thing in Potosi.

The Mountain That Built A Rich City

The mines here helped turn this into an Imperial City, as the Spanish called it, as big and rich as Madrid. Though the wealth has faded since colonial times, there are still opulent churches and old mansions that attest to the city’s glory days.

The Spanish called the mountain Cerro Rico, or Rich Mountain, for the silver they extracted from the mountain. Some 3 million Quechua Indians were put to work here over the years. Hundreds of thousands died, casualties of cave-ins, or killed by overwork, hunger and disease.

Today, deep in the bowels of the mountains, little appears to have changed. Up to 16,000 miners toil here much like their ancestors did, using picks, hammers, shovels and brute strength. Men and boys — sons of the miners — haul rocks to the surface on their backs. There are rail cars, but they are the old iron ones introduced to mining in the 19th century. There’s no lighting aside from workers’ headlamps, and no piped-in oxygen or safety regulations.

“There’s nothing for us, just for the bosses,” Marino says. “We work like mules, like slaves.”

The paradox is that it’s the miners who are in charge: There are 35 cooperatives, owned and run by Quechua Indians.

But the miners here say it’s the managers who take the lion’s share of the revenues from the mining of lead, zinc and the silver that’s left. The government, dependent on support from mining cooperatives nationwide, has been reluctant to get involved.

Pride, And Suffering

Nonetheless, mining families here remain proud of their role in the mine. They live in a rough-and-tumble neighborhood called Calvary, at the base of the mountain. They frequently put on big parties, complete with brass bands and plenty of food and beer.

The hard truth, though, is that mining inside the Rich Mountain means hardship and hellish conditions. The miners have to lower themselves down rocky, tight holes barely big enough for a grown man. And then they spend hours heaving and hauling, all at an altitude of 14,000 feet. Invariably, they wind up old and broken down before they’re 50.

“We can’t hack it like when we were young,” says miner Elogio Tola, who’s 45. “We get tired more easily.”

Even if the miners survive cave-ins, Tola says they know death will come from the fine deadly dust they breathe daily.”

Article by JUAN FORERO

We arrived in Potosi early evening at what must have been Bolovia’s nicest bus station, then jumped into a very comfortable Nissan taxi before being whisked off to a new hostel. All well above our expectations for such a poor area of Bolivia. Hostal Eucalyptus, part of Koala Tours and the Koala Den, gave us a great room with breakfast and more than adequate internet for Andrea’s Friday morning work. We decided to use Koala Tours for our mine tour instead of Big Deal Tours – my choice as they seemed to offer a better escape plan if claustrophobia kicked in!

I had been nervous about today ever since we decided to visit Potosi, especially after hearing so many reports about how small and tight the tunnels were in the mines. We still bit the bullet, paid the 100 Bs or just over $14 each and headed off with a bunch of other foreigners to change into our mine attire. For the two hours we spent in the mine, we had better protection than the miners who work for up to twenty four consecutive hours wearing only regular clothing with a helmet, and either a gas or electric light. We also bought ‘El Tio’ bandanas to protect our lungs from the deadly Silicosis causing dust.

“Ceibo, Coca Leaves and DYNAMITE”

Inside Candelaria Mine

It’s hard to understand why outsiders are so curious about visiting these mines, sometimes penetrating three kilometers through the mountain. Well we were now part of that curiosity turning up at the mine entrance set amidst clay brick huts with empty Ceibo bottles and trash all around. It was three in the afternoon and there were wasted miners sitting around still drinking with their cheeks puffed out full of coca leaves. Our lights were turned on and we entered the small archway, splattered with llama blood from previous sacrifices to El Tio, the devil so highly worshipped for providing safety and lucrative veins of minerals throughout the mine.

We were only on the first level some five hundred meters or so inside the mine and some parts were already getting narrow with sketchy looking roof beams. This part of the mine has tracks for the excavated minerals, something we were always on the listen for as the carts don’t stop for tourists! Most of the miners we met were just hanging out inside the mine, passing around bottles of 96% Ceibo and stuffing their cheeks full of coca leaves, used to counter the effects of fatigue, high altitude and hunger – no food is taken into the mine as the dust is too relentless.

A few hundred meters farther in, we took a very narrow tunnel down past the second level and on to the third level – we had no choice but to scoot down on our butts for fifty meters, something I was not enjoying so much! I decided to head back to the first level, crawl inside a tight cave with some new Potosi friends and do what the miners do best with liquor and leaves. Andrea continued down the very hot third level to meet other miner’s. On the way out of the mine one member of the group wanted to venture down the extremely tight passageway to the second level to actually see miners drilling. A loose rock landed on Andrea’s arm and that was enough for her to bail on level two. After the tour we all met outside where I had found more miners to share L&L with – what a great day!

July 25th – July 26th 2013